Causes of Pain following Shoulder Surgery:

Like a lot of folks who have had shoulder surgery, I've spent many moments (too many) trying to figure out what's hurting and why so that I might be able to make it better. So as nothing much has changed with my recovery this week, I thought I'd share some of my ideas and research into these causes of pain. I am not a doctor, by the way. You're mileage may vary, the value of your investment may go down as well as up etc etc.1. Incisions: These things hurt - even the little arthroscopic ones. Having had both arthroscopic and open surgery - and combinations of the two - my experience is that they all hurt. The medical profession sells us the benefits of arthoscopy (keyhole) as faster recovery, less scarring, but it's more complex than that. Arthroscopy carries lower risk of infection, less blood loss and less risk of the wound opening back up after surgery. Open surgery is typically one large incision whereas with Arthoscopy, between two and five separate incisions are made - that's up to five separate points of pain. The rise in the use of Arthroscopy has meant surgeons can visualise, diagnose and treat many more conditions than they could before - but I would still wager someone with five arthroscopic incisions has more pain than someone with two. Even when the incisions appear to be 'healing nicely' there is still the disruption to the deltoid muscle beneath and this can still cause some pain for two or three months.

How to minimise this pain: Gentle massage of the healed incisions (usually 3 weeks onwards) helps to break down and soften the scar tissue that forms beneath. Do this a couple of times a day for about 6 weeks - remember to wash hands first! Don't massage an incision that is bleeding, weeping or very painful to the touch otherwise you may introduce an infection or cause damage.

| Open | Arthroscopic |

|

|

|

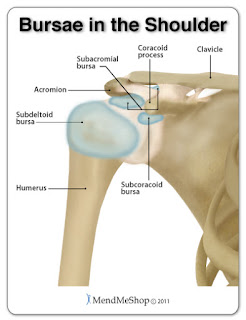

2. Busa Removal: The soft lubricating sack that sits between the rotator cuff and the deltoid and allows these opposing surfaces to move smoothly against each other. The bursa is nearly always inflamed and scarred when a rotator cuff tear or sub-acromial impingement is present. The surgeon will remove most or all of it during surgery, however it grows back within about three months. I'm sure this hurts, although there is little research to back up this idea. Consider also that the deltoid (with incisions in it) and the rotator cuff (with sutures and anchors it) are now touching without the bursa to keep them apart, so there's bound to be some pain from this in the early stages of rehab.

How to minimise: This is pain that has to be worked through. Begin passive movements as early as you are allowed. Ask your physio about stretches to restore range of motion and stick to the program. Regular movement will encourage the regrowing bursa to find it's way back to where it needs to be.

3. Healing of the Repaired Tendon: Repairing a tendon back down to bone involves passing sutures (stitches) through the tendon that are fixed into the bone either with anchors or holes drilled into the bone. The bone is also abraded down to make it bleed slightly which promotes healing. In some cases, small holes are made in the bone (microfracture) where the tendon fixes down which promotes the release of bone-marrow which also promotes healing. All of this disruption to tissue and bone causes a healing response which results in pain and inflammation. This improves as the tissue and bone heal, but given the slow healing of rotator cuff tendons, this may take many months.

How to minimise: There is little one can do to minimise this pain, other than to follow the recovery protocol set by the surgeon to give the best chance of good healing. Generally this involves immobilisation for 3 to 4 weeks, followed by passive exercises to restore ROM, followed by active movement at around 6 weeks to restore function, with strength rehab beginning at around 10-12 weeks.

4. Capsular Tightness: Beneath the rotator cuff there is a capsule of ligament tissue surrounding the ball and socket joint. This helps stabilise the joint, but it can cause problems if the shoulder is kept immobile for a long time as the capsule can shrink. This results in a tight shoulder that is difficult and painful to mobilise. Some people with limited ROM at three months following surgery are told they have a frozen shoulder. This is because a frozen shoulder is caused by a tight and inflamed capsule, so the cause and symptoms are almost identical. However, even if you are able to coax your ROM back, you will still go through a period of stretching the capsule and this can be quite painful. I've encountered this myself as a deep aching that seems to lessen considerably once full range has been established.

How to minimise: Again, this is pain that has to be worked through. Begin passive movements as early as you are allowed. Regular stretching without undue force is key. Forceful stretching is likely to aggravate this pain and is never recommended prior to ten weeks post-surgery anyway.

5. Scar Tissue and Adhesions: As the soft tissue in the shoulder heals and recovers, it forms scar tissue, much in the same way as an old cut or burn may be visible on your skin. If you are immobile (in a sling) for a long time, the risk of some of these bits of scar sticking together (adhesions) increases. If they are allowed to establish, these adhesions can restrict range of motion - a condition known as captured shoulder; I have had this myself. In captured shoulder the bursa gets stuck to the healing cuff and literally gets dragged around inside the shoulder as you move, becoming inflammed and painful in the process. Adhesions that don't resolve with physiotherapy can be removed during an arthroscopic debridement, which usually works well. However, in the early stages of recovery you will always get a few adhesions which you can hear snapping and popping as they resolve; which is a good thing, as long as they continue to break up.

How to minimise: Pain from adhesions and scar is less obvious and can suddenly onset (and resolve) with certain movements. Very often you can feel adhesions break as you stretch (snap/pop) and they are followed by a sense of relief. Maintaining a good range of ROM as early as possible helps to stay on top of the formation of these bits of adhesive scar.

Brief Article describing Captured Shoulder: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8864004

6. Trigger Points: Sometimes called muscle knots, these are painful little points of tension in a muscle or tendon. They can usually be resolved by applying pressure through the skin, either with the sharp point of a finger or by lying on a tennis ball, or better still, a lacrosse ball - but it is best to wait until you're out of the sling before trying this. An operated shoulder can be prone to these knots as the muscles suddenly find themselves unstretched for long periods or when certain muscles have to compensate for others. The infraspinatus muscle in the shoulder can be particularly prone to trigger points as it compensates for a torn or weakened supraspinatus. Sometimes these trigger points can be difficult to treat, especially if they are chronic or in muscles that are difficult to reach through the skin, such as the supraspinatus and the subscapularis. Dry needling or acupuncture is particularly effective at reaching these painful trigger points and I would recommend seeking the help of a chiropractor or osteopath who practises these techniques.

How to minimise: Ask your therapist about treating trigger points with a ball. There are numerous YouTube videos on this, but seek professional advice to avoid hurting yourself and wait until you're out of the sling.

In conclusion: I guess the mantra here is 'keep moving'. The longer a shoulder is immobilised, the harder it is to get it moving later. I have read a number of stories of surgeons who insist on keeping some patients immobilised for 8 or 9 weeks following rotator cuff repair. Their reasons for this are usually to do with poor tissue quality found at the time of surgery. However, the pulling and stretching required to get a shoulder moving after 8 weeks of immobilisation exposes a repair of poor quality tissue to even more risk of retear; as has been my own personal experience. Using an allograft to augment such repairs means the patient can mobilise their shoulder earlier with a better chance of a successful rehabilitation. If your surgeon doesn't do this kind of procedure, find one that does.

Thank you for documenting your shoulder's journey. I'm sure many people will find this very helpful!

ReplyDeleteLet's hope so :-)

ReplyDelete